I've handed over the reigns to Gareth again today. He's taken a slightly different approach to his article this week: he's going to take a closer look at a photographer he admires, and examine just what it is that does it for him.

All yours, Gareth...

A Closer Look is a series of articles looking at the work of photographers whose work means something to me. When I am influenced by the work of others, I like to take less tangible elements away from the images. It isn't useful, in my opinion, to closely study the technical style of a given photographer, as you are at risk of losing your individuality. A more useful practice is to study what you love about an image beyond the immediately visible.

This week, I'm looking at Jonathan May, a photographer I became aware of when he was selected as a finalist in the National Portrait Gallery's Taylor Wessing 2011 Photographic Portrait Prize.

A small disclaimer: just because I admire May's work doesn't necessarily mean I can speak about it with authority – I merely aspire to describe what I like about it.

The first thing that strikes me about May's work is that it's often very positive in tone. This is extremely refreshing in the current climate, because so many photo stories, whilst absolutely beautiful and shot with a mastery that leaves me open-mouthed, are of subjects that are, frequently, unrelentingly bleak. Now don't get me wrong, I think it's vital for photography to be able to highlight issues and tell stories that would go untold and unseen by the world. Not only that, but I think the people who bring such stories to the world are genuine superheroes (and possibly slightly unhinged): it's just that the saturation of such stories makes me yearn for something different.

You can see this immediately in his set L'Afrique. I feel that, in the West, we have a skewed image of Africa: a combination of the doom and gloom of the media and the plethora of photo projects that cover injustice, poverty, war and political horrors throughout the continent. It feels like from north to south, east to west, it comprises misery and human suffering. There is, of course, much of that, all of which needs to be exposed to the world and not kept a secret, but there is also a vast and beautiful culture and history which is seldom celebrated in the face of documenting all that is wrong with Africa.

May's shots of Africa exhibit a warmth, respect and admiration for African culture. It is refreshing to see a story of Africa that feels more celebratory than exploitative: in L'Afrique we become students, soaking in the beauty, gazing up at these people, learning, engaging on a human level.

The most important skill exhibited in L'Afrique is May's ability to act as the humble recorder whilst still applying his style, skill and proficiency to the images. If an image evokes more of the photographer than it does the subject, it's doing something wrong, in my opinion. This is something May is acutely aware of and he elevates his subjects whilst remaining anonymous to us, the viewer.

It's a feeling May achieves in many of his projects and is something evident in any story he tackles. I love his ability to find beauty in topics and stories that are infrequently covered. This is why one of my favourite photo stories of his is Greens: a look at crown green bowling, more specifically the bowling club his grandfather founded.

There is something quite beautiful in the telling of a story through the paraphernalia and objects that surround the people involved in the story, and Greens achieves this beautifully. An image of a somewhat chintzy clubhouse carpet with a table occupying the corner tells us as much as a one of his intimate, shallow depth of field portraits does. It's when these two are combined in a series that they unlock the power of one another: although they are strong images on their own, the effect is compounded when they are brought together, contrasting as they are in content.

As a portrait photographer halfway through my first ever long-term photo project, I am fascinated with the idea that a portrait of someone can be greatly enhanced by an image of their surroundings, or of something that is illustrative in some way of who they are, as opposed to a single image of the actual person.

There are dozens of single images within Jonathan May's work that I love but, in the interests of not making this article tediously enormous, I will look at my absolute favourite and attempt to articulate why I adore it.

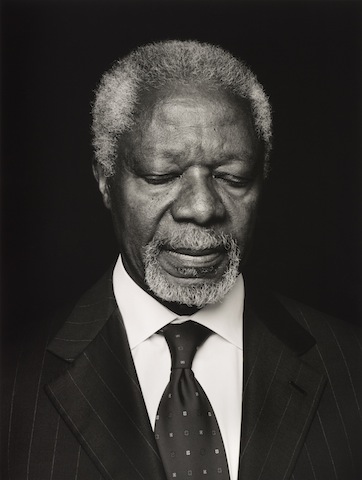

This is a portrait from May's series Caravans, a story about a society that is often looked down on and dehumanised in many ways. The series itself has all the trademarks of May's work, but there is something about this particular portrait that, as I cycled through the images, was like a punch in the stomach: a good punch in the stomach, if that makes sense (it doesn't).

Initially, the intimacy of the composition grabbed me, so I brought it up in full screen. The background is uncluttered and plain yet far from blank: it further draws us to the subject's face. The expression that May has captured is utterly captivating: it's an expression that is both inscrutable and full of emotion at the same time. His mouth is ever so slightly curled up at one side, suggesting a smile may be breaking out. There is the tiniest hint of a wet glint in his eye, as if he is holding back a tear, but it's all so slight that we're not sure whether that is a projection of what we are seeing in his face or the reality of the situation. When I look at his face, I see a man remembering: an expression of fond reminiscence. We are the ones to lay down the final brushstroke, the canvas is left open for us.

And 'canvas' is an appropriate word here: the mesh of the door has muted and diffused the light and the wooden frame forms the right hand side of the image, creating the feel of a Renaissance-era painting, faded over time. I love the idea that something so beautiful can come from a seemingly innocuous shot of a man looking out of a window in his caravan. That, dear readers, is the magic of photography.

What I'd really like is for these columns to become discussion points about the artist in question. I want to hear what you think of Jonathan May's work – does it resonate with you? Does it excite you? Does it bore you? What do you like? What do you hate? Let's hear your opinions!

The illustration was by the mightily talented James, of Sweet Meats Illustration.

You can check out Gareth's photography here.

And if you're wondering about the copyright implications of reproducing May's work in this article, it's covered under fair dealing, as criticism and review.

Margarita Teichroeb by Jordi Ruiz Cirera. 1st Prize (Copyright Jordi Ruiz Cirera).

Margarita Teichroeb by Jordi Ruiz Cirera. 1st Prize (Copyright Jordi Ruiz Cirera).