It’s early autumn so everyone has leapt aboard the Christmas juggernaut, God help us. Christmas isn’t just celebrating half-a-dozen similar but morally incompatible festivals of religious and secular nature.

If you create electronic equipment, it’s also (not to mention ‘mostly’) about making berkovets of cold, hard cash.

Needless to say, the photographic world conforms to this standard. This week alone, four camera manufacturers released five different cameras. Nothing unusual there, then (however much I wish the festival frenzy was restricted to seven days immediately prior to 25 December). But take a second look at these cameras, and listen to the rumours coming out of both Canon and Nikon, and you’ll notice that there’s an interesting trend emerging: A movement away from the angelic (D)SLR – or (Digital) Single Reflex Camera we all know and love, and an elegant hop towards mirror-less, or EVIL (Electronic Viewfinder, Interchangeable Lens) camera bodies.

Trend? Whatyoumean trend? I see no trend!?

Some trends come in oddly-photographed packages

The observant amongst you will have spotted that only one of the five new cameras that were launched this week was of the mirror-less variety: namely the Samsung NX100. That’s hardly a trend, is it? Well, no. But some other interesting things have been going on. Olympus’ E-5 is its new flagship camera, but as I said over on Small Aperture, I don’t think that they’ve done justice to the camera that is supposed to be heading up their range. Nothing about it makes me go ‘Wow!’ and reach for my credit card. As a self-confessed camera geek, that’s pretty much the reaction I’m expecting when new camera equipment gets let loose. The Nikon D7000, released the same day, is far better value for money than Olympus’ new flagbearer.

It’s not just the uninspired E-5 that suggests Olympus will soon be ceasing production of SLRs, but squeaks from within the camp are saying something similar.

Quite apart from the retro-tastic tiny swivel-scrreen, the Pro90 used an EVF - or Electronic Viewfinder.

If the murmurings from ‘the other’ manufacturers aren’t convincing enough for you, listen to the rumours from Canon and Nikon. Neither of these behemoths of the optical world have produced current-generation mirror-less cameras yet (although both Canon and Nikon have created ELF – Electronic View Finder – cameras in the past, with varying success. Photocritic editor Haje notes that he had a Canon Pro90 about 10 years ago, but ended up trading up to a ‘true’ SLR, because it was ‘pro’ only in name – not in actual fact), but perhaps that could be about to change?

The intergoogles are awash with images of the Canon EVIL, and its prospective range name: EIS. There’s a strong hint that Nikon will announce a mirror-less camera, Q, at Photokina this month. So I’ll say it again: mirror-less cameras.

What is this mirror-less camera you speak of, Miss Bowker?

I should probably begin by saying that in a way, ‘mirror-less camera’ is a bit of a misnomer, after all, compact cameras do not have mirrors either. But the problem is that no one has been able to settle on a name or even an acronym for this other breed of magical-picture-making-machine that benefits from interchangeable lenses but doesn’t have the bulky mirror fandango of the SLR. You might hear them referred to as Mirror-less Interchangeable Lens Cameras (MILCs); Digital Interchangeable Lens cameras (DILs); Micro cameras; Single Lens Direct view cameras (SLDs); or my personal favourite: Electronic Viewfinder Interchangeable Lens cameras (EVILs). In the absence of any generally agreed term, I’ll stick with mirror-less camera.

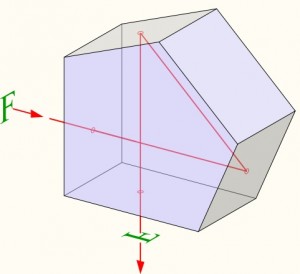

In order for the mirror to be able to flip out of the way, there has to be a gap between the imaging sensor and the lens. Mirrorless camera designs do away with this gap.

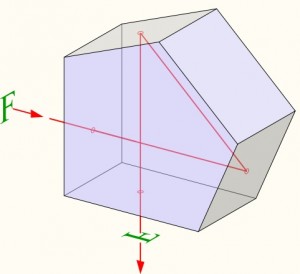

Anyway, if you want to know how a mirror-less camera works, you need to know how an SLR, or single lens reflex camera, works first. It’s pretty simple, actually. When you take a picture, you need to be able to see what your lens is seeing otherwise you’ll be decapitating your portrait subjects and accidentally omitting the most interesting feature of your Italian vista. With an SLR, there’s a mirror that redirects the light seen through the lens to your eye, via the optical viewfinder. When you press the shutter release button, the mirror flips out of the way and the sensor (or film, if you’re feeling retro) is exposed to the light and therefore the image. Tah-daa, there’s your picture.

As the term ‘mirror-less’ so aptly reflects, these cameras don’t have mirrors to redirect the image through to your eye via an optical viewfinder. Instead, you see the image on an LCD screen, or an electronic viewfinder, if you’re really lucky. The lack of the mirror malarky reduces the size of the mirror-less camera when compared to an SLR, yet you still get all the goodness of the flexibility of interchangeable lenses and a big sensor.

‘Awesome!’ people might be thinking. Muchly-flexible, muchly-smaller camera. Well, not quite.

Drawbacks of the mirror-less camera

We use SLRs because they give us so much control over the pictures that we shoot. It’s not just about the range of lenses, because, hell, the mirror-less cameras are offering that. It is about the mirror-less camera not autofocusing as fast and having a slower frame rate than an SLR. In addition – at least in our SLR-accustomed eyes, it is about the mirror-less camera being less comfortable, and less intuitive to use when composing pictures using an LCD screen.

In your SLR camera, you'll find the pentaprism in the 'hump' at the top of your camera, just by the eye-piece. It adds to the bulk of your camera (which is bad) but enables you to 'preview' what you are photographing, literally at the speed of light (which is good). If camera manufacturers instead had used a mirror (which would have taken up less space), you would be looking at the world upside down, which would have given a mighty confusing photography experience.

That screen adds an extra layer of communication between you and your image. If you’re a sports or wildlife photographer – or indeed a photographer with any interest in action shots – a mirror-less camera is just not going to be fast enough for you. With a mirror, you are optically connected with your subject, and you get the information you need at the speed of (dare I say it…) light. In other words: you need that mirror.

Compare a mirror-less camera to a high-end compact camera and you’ll notice that perhaps a mirror-less camera isn’t as small as you thought it was. Sure, there’s no more bulk from the mirror, and the pentaprism is absent, but the lens is going to add something significant that the compact does so well in hiding away. You’re never going to be able to pocket a mirror-less camera the same way that you can a Canon S95. This ‘smaller, more portable’ selling point is probably going to have to be re-thought.

In addition, I’m not completely convinced that sensor- and monitor technology is as far advanced as we need it to be. If you have a current-generation dSLR, you may have a feature known as ‘live view’ – this flips the mirror out of the way and lets you use the display on the back of the camera as a viewfinder. For some applications, this works great, but, well, not always.

“I decided to try shooting using only Live View on my 550D for a whole day”, says Haje, editor of this fair blog, “But I gave up after about an hour. I know the 550D probably isn’t the pinnacle of Live View / Electronic Viewfinder technology, but for the technology to become even remotely interesting, it has to be drastically improved. In three years, perhaps. Right now, I’ll stick with the speed of light, thanks.”

Positives for the mirror-less camera

Despite me clattering the mirror-less camera ideal, it does have at least one noticeable positive: lens flexibility. Historically, photographers have bought into a brand because they favour their lenses.

Canon lenses fit Canon bodies and Nikon lenses fit Nikon bodies. (Yes, you can buy generic brand lenses, too, but the mount will still be brand-specific.) Cross-over only happens with the use of an adapter, but the adapter can place the lens too far away from the body and that presents focusing problems. However, the smaller size of the mirror-less camera means that the adapter doesn’t place the lens so far from the body and focusing is no longer a problem. Say hello to lens cross-over, in the style of the moderately successful Four Thirds standard, where Kodak, Olympus, Fuji, Panasonic, Sanyo, Sigma, and, (with a camera manufactured under licence by Panasonic) Leica have joined forces to try to create an universal lens mount and pool their imaging sensors.

The Olympus Pen has an optional viewfinder attachment, turning it into the bastard lovechild of a SLR camera and a rangefinder. Which might not be such a bad thing, actually...

There are a few other cameras out there that do similar things. Digital rangefinders, like the Leica M8 and M9, for example, don’t have mirrors; they rely instead on a different camera design and educated guesswork to get the images the way you want them. Rangefinders, however, are usually met with a Marmite-like effect: You love them and you’ll sell your firstborn to be able to afford the ridiculous price-tag for a Leica M9, or you can’t get along with them, simply because they aren’t SLR cameras.

The mirror-less cameras may be at an advantage by taking the good things about rangefinders (the fact that the lenses can be closer to the sensors because there is no mirror between is a huge benefit, optically) and SLR cameras (much cheaper components, great, well-tested sensors, and an enormous range of lenses available), and merging them in a lovely, uniform package.

What does this mean for photographers?

You know, I don’t think that mirror-less cameras are going to have some great revolutionary impact on the industry or on photographers. Not really. They’re not efficient enough for some types of photography and they’re not small enough to present a serious challenge to high-end compacts. And I don’t think that lens cross-over is a big enough selling point on its own.

There probably is a place for mirrorless cameras in the photography landscape, but I don't see guys like this making the switch in the foreseeable future. (photo by Mike Baird, click to see full size)

Olympus might be leaving the SLR market behind, but if it does, it could well be that it is keen to try to carve itself out a niche after the brand has recognised – after a long and valiant battle – that they simply can’t compete with the rest of the marketplace.

Regardless of Olympus’ strategic direction, I don’t see Canon or Nikon abandoning SLR technology in a hurry, and neither do I see photographers deserting SLRs in droves. What the mirror-less camera does do, is to give consumers more choice and the manufacturers the impetus to push the boundaries with compacts and SLRs. Either way, I think it’s safe to say that mirrorless won’t be the revolution that’ll reduce the our humbe SLR servants to a niche equivalent to where we see film photography today.

And honestly, if the manufacturers want this one to catch on, they have to settle on a universally recognised name. Marketing is all about your consumers being able to identify with your product. At the moment, consumers can’t even make sense of what the product is, much less where it fits into their photographic arsenal.

This post was written by Daniela Bowker, who normally serves as my trusty side-kick as the editor of the Small Aperture photography blog, with a lot of input and second opinions from myself.

Do you enjoy a smattering of random photography links? Well, squire, I welcome thee to join me on Twitter -

© Kamps Consulting Ltd. This article is licenced for use on Pixiq only. Please do not reproduce wholly or in part without a license. More info.