Without the easy-to-lose piece of plastic, your FujiFilm charger is useless. Let's go DIY on its ass...

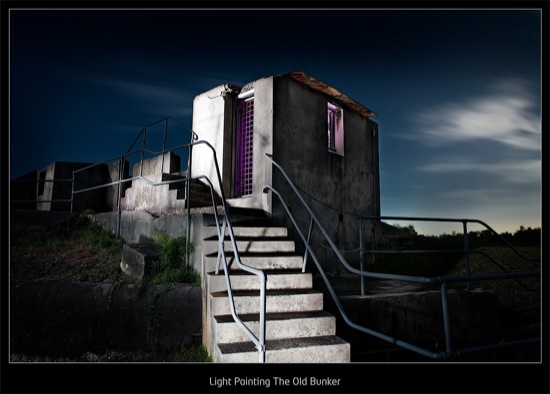

I've had a FujiFilm X100 for a while now, and I still don't completely know how I am getting on with it. Sure, I have taken some rather fabulous photos with it, like these ones:

The FujiFilm X100 battery charger problem

But it is not without its niggles. One of the small but incredibly annoying problems with the X100 is that the battery doesn't fit in the battery charger that comes with it. I know, it sounds completely inane, but it's true: To use the X100's battery in the charger, you have to use a tiny piece of plastic in the charger. Without it, the battery fails to make a connection, and won't charge properly. FujiFilm, if you're reading this: That was a complete bonehead move, and you really ought to be ashamed of yourself.

However, as a DIY photographer, I figured this was my chance to make my own life better. I lost the little piece of plastic nearly immediately, and was using toothpicks to hold the battery in place, but when my good friend Sarah told me about Sugru (by the way, Sugru, if you are reading this you should totally hire Sarah. She is awesome. Also, if you aren't reading this, then you obviously need a new community manager. Which brings me back to my original point: Hire Sarah.), I immediately saw a great use for it: Finally, a way of fixing my X100 charger, permanently and once and for all.

Let's get busy!

So here, offered as a deliciously simply to follow step by step guide: How to fix your FujiFilm x100 charger, by the power of Sugru:

1) Make sure you clean your charger properly; The Sugru is pretty hardy stuff, but if it's dusty or greasy, you're going to get less of a bond:

2) Take two small balls of Sugru (this was about 1/8th of a 5g packet of Sugru - or a grand total of £0.17 / $0.26 worth), and shape them into, er, balls.

3) Insert the battery into the charger, to make an imprint into the Sugru. Push it into the Sugru ever so slightly, and then remove the battery. The material will keep the shape you've just made, and harden over the next 24 hours.

4) Use a wet finger to gently brush off any excess material. Sure, this is an optional step, but if you're going to hack your own camera equipment, you may as well make it look reasonably good.

5) re-insert the battery to make sure it still fits properly, then remove it again

6) Leave it to harden for 24 hours

Congratulations! You've spent pennies on fixing a problem that FujiFilm really should have done right in the first place. More importantly, you can now use your well-earned bragging rights down in the pub, telling everyone that you've improved a piece of your own photography gear!

If someone tells you “LOL learn how 2 autofocus, you dweeb”, you need to do 2 things: Live in the happy knowledge that whilst your camera might have had an off day, at least you know how to string a grammatically correct sentence together.

If someone tells you “LOL learn how 2 autofocus, you dweeb”, you need to do 2 things: Live in the happy knowledge that whilst your camera might have had an off day, at least you know how to string a grammatically correct sentence together. Ultimately, you are the photographer, and what you decide is how the final result gets done. Nobody can tell you what to do, and if you like your photo, then you’ve won one of the huge battles.

Ultimately, you are the photographer, and what you decide is how the final result gets done. Nobody can tell you what to do, and if you like your photo, then you’ve won one of the huge battles. It’s the curse of all writers and poets: They spend months – years, even – crafting their masterpiece, and then nobody ‘gets’ it. They all ‘get it’ wrong. Tell you what though, that’s where part of the beauty comes from: If you are taking a photo which you meant to symbolise the innocence of youth, and your first 10 commenters feel it’s a strong commentary on, say, child abuse, then they are per definition right.

It’s the curse of all writers and poets: They spend months – years, even – crafting their masterpiece, and then nobody ‘gets’ it. They all ‘get it’ wrong. Tell you what though, that’s where part of the beauty comes from: If you are taking a photo which you meant to symbolise the innocence of youth, and your first 10 commenters feel it’s a strong commentary on, say, child abuse, then they are per definition right. Remember that, just like you are not there to interpret your work, you’re not there to defend it either.

Remember that, just like you are not there to interpret your work, you’re not there to defend it either. Technical aspects of your photographs might be objective: A photo can be accidentally over-exposed, blurry, or have some rubbish in the background which makes your photograph less-than-perfect. Once you start killing the technical foibles of your photographic work one by one (don’t go too perfectionist on it though, it’s not useful to end up deleting all of your photos because of every little detail), the actual creative work starts shining through, and this is where the worst potential for getting hurt comes from.

Technical aspects of your photographs might be objective: A photo can be accidentally over-exposed, blurry, or have some rubbish in the background which makes your photograph less-than-perfect. Once you start killing the technical foibles of your photographic work one by one (don’t go too perfectionist on it though, it’s not useful to end up deleting all of your photos because of every little detail), the actual creative work starts shining through, and this is where the worst potential for getting hurt comes from.