The English Premier League kicks off tomorrow and in addition to last minute transfer news, shock managerial sackings, and managerial press conferences, copyright and broadcasting rights and the use of tablets inside Old Trafford have made headlines, too. The issue of tablets and laptops inside Old Trafford is fairly self-explanatory: Manchester United has prohibited bringing them inside the grounds owing to security reasons. The copyright issue seems to have people in more of a flap. And heavens, this isn't the first time it's happened. The Premier League has stated that it will be taking action against people who compile and share Vines of goals that they record from live broadcasts of matches. Being able to live-pause broadcasts makes this relatively straightforward technologically, but it's a breach of copyright.

This has thrown up a few interesting questions, not least from the BBC's Technology Correspondent, Rory Cellan-Jones, who wondered if his Google Glass recording of Brentford matches would violate copyright.

https://t.co/TIbfR6kft6 Now worried about my Brentford through Google Glass video - am I in copyright trouble?

— Rory Cellan-Jones (@ruskin147) August 15, 2014

I'm fairly certain it wouldn't violate copyright, but it could well infringe on other rights. So if everyone will be please calm down, and preferably sit down, I'll explain what (I think) the situation is.

Copyright

Copyright is the right to make copies of someone else's creative endeavours. When I click the shutter on my camera, I own the copyright to the image that creates. When BT Sport or Sky Sports record and broadcast a football match, they own the copyright to the broadcast. That is, the producer decides on which cameras to use and how to put together their sequence of use, which constitutes the original work. The football match itself isn't copyrightable, it's the broadcast of it that is.

As well as charging their subscribers a fee to watch the matches, BT Sport or Sky Sports can charge other broadcasters to use these images or they can keep them all theirselves. Their pictures; they decide.

When someone sitting at home on the their sofa and watching a football match compiles a Vine of the goals using pictures transmitted by BT Sport or Sky, they're violating BT Sport's or Sky's copyright. They are taking BT Sport's and Sky's work and using it without permission and without paying for it.

When you read that BT Sport and Sky Sports are complaining about their copyright being violated, this is what they mean.

Broadcast rights

When BT Sport and Sky Sports won the contracts to televise Premier League matches, they paid an excruciating sum of money for broadcast rights, or the opportunity to transmit live pictures from the game. The BBC holds the broadcast rights to highlights of the Premiership matches. They paid a fair whack for that, but not quite as much as BT Sport and Sky Sports. This season The Sun and The Times have the online rights; this is big business and it's this money, paid to the Premier League, which has made it into the financial behemoth that it is.

Turning up at Old Trafford or Stamford Bridge and taking photos or video of a match would get you into a different type of trouble, therefore. If you were to try to stream the match live from your seat, you wouldn't be very popular with a gaggle of corporate lawyers for infringing on broadcast rights. Not to mention you'd likely upset the fans sitting around you if you obstructed their view. Whether or not you can take a camera into a football stadium and take some photos for personal use seems to be open to clubs' interpretation. It's worth checking what it says on the ticket. Some might be happy for you to take a photo to remind yourself of the day; others might want to throw you out for just having a camera.

Broadcast rights and copyright are different beasts, but from the same genus. You'd own the copyright to any images you were fortunate enough to make inside a stadium, because you'd made them. What you wouldn't own are the broadcast rights to let you redistribute them. Not unless you'd paid an eye-wateringly large sum of money for the privilege and you probably don't have enough kidneys for that.

Performers' rights

Back to Rory Cellan-Jones and his tweet asking about copyright violations at Brentford, someone asked if it wouldn't breach performers' rights. No. As far as I can tell, performers' rights don't extend to sporting events, at least not in the UK, so there would be no infringement there.

Tablets

Now we get onto Manchester United's prohibition against tablets and laptops inside Old Trafford, which was announced earlier this week. According to officials there, the decision to ban larger devices, including iPad Minis, was made in response to security concerns. They're worried someone might want to pack a bomb into a device, much like airlines are. The ban doesn't extend to smartphones, provided that their dimensions are no larger than 15 centimetres by 10 centimetres (5.9 inches by 3.9 inches). Seeing as smartphones have not been banned and they're still capable of taking photos, we'll take this one at face value. And quite frankly, if it stops people obscuring others' view with when they're recording with the iPads, so much the better.

In conclusion

Please remember that I'm not a lawyer. I'm a writer who takes a fiendish interest in copyright and I've applied a healthy dose of common sense to its ramefications, together with a bit of research.

If you want to take photos or video at any sporting event, I suggest that you check with the stadium before you turn up with any manner of kit. You don't want to forfeit your ticket or have your gear confiscated. Speaking from experience, just go and enjoy the game. Fiddling about with electronic equipment detracts from the atmosphere and what's happening in front of you - the reason why you're there. But maybe that's for another article.

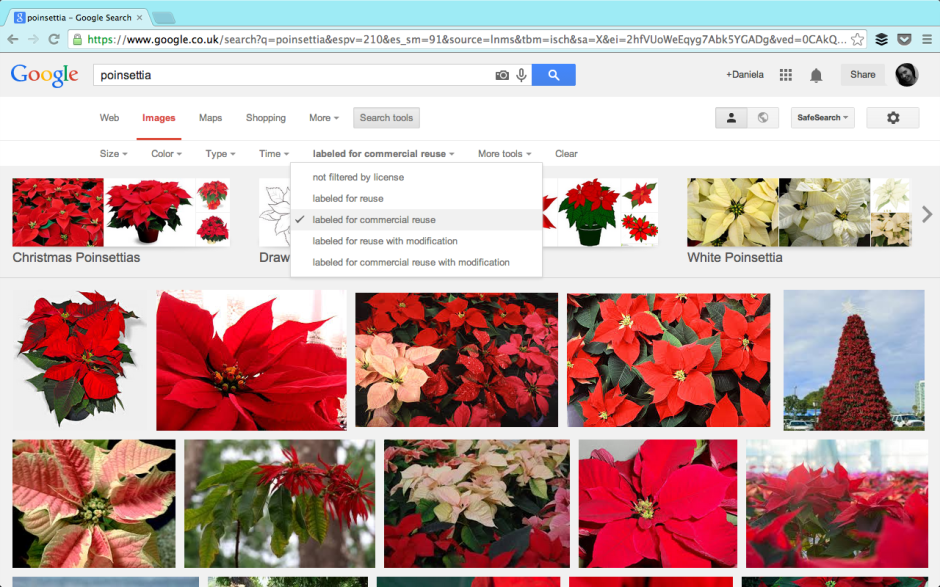

When it comes to making Vines from what you can see on TV - don't. Protecting intellectual property applies to little guys as much as it does to big guys. If we don't want them stealing our content from social media sites and using it for free, best not to infringe their copyright either.