Doesn't ask doesn't get. If you see something that you don't like or you believe is wrong: say something!

Just because you found it on the Intergoogles it doesn't mean it's free to use

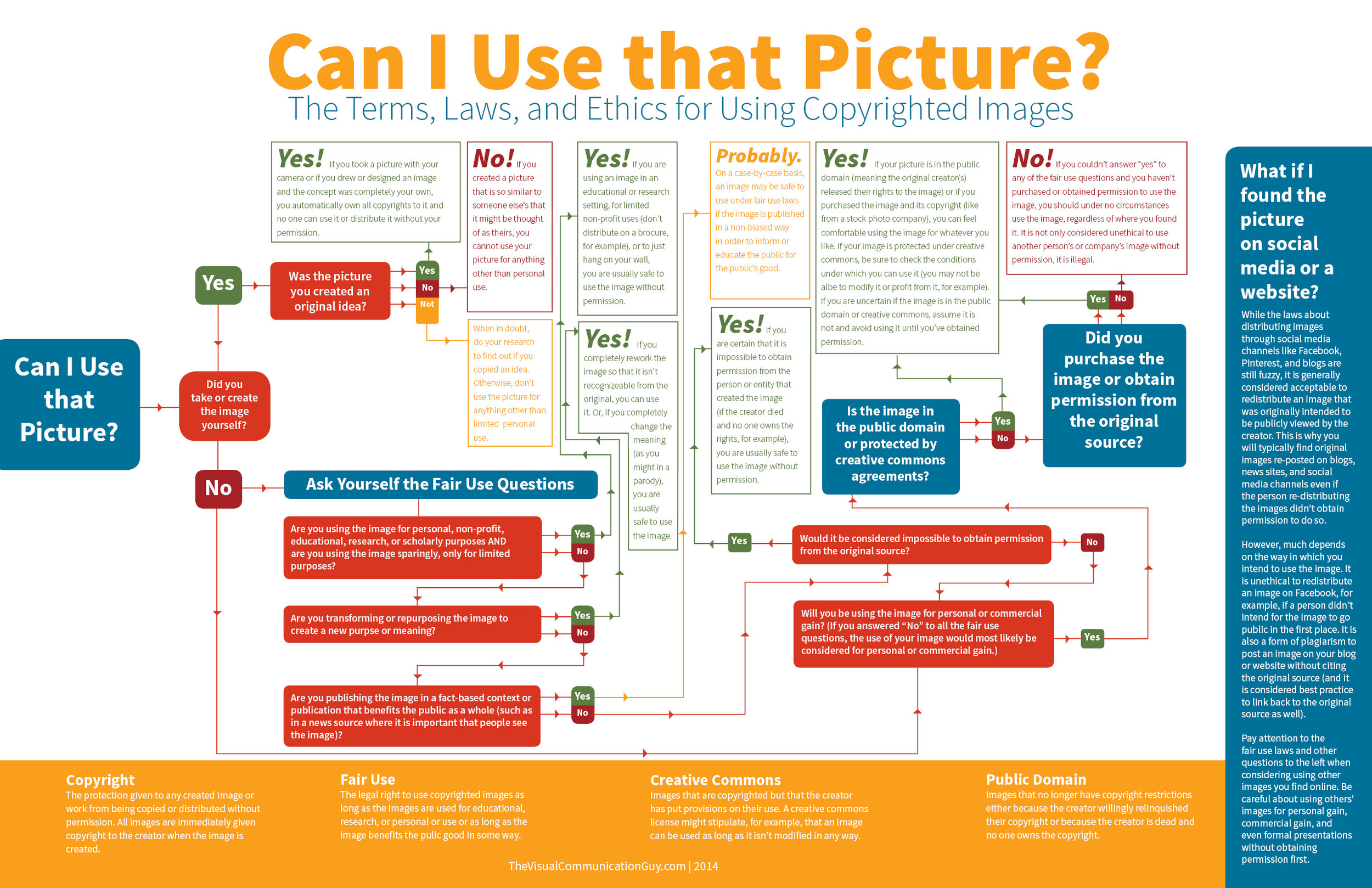

I was having a fairly good morning, until I took my lunchtime peruse of Feedly to see if anything interesting or exciting had dropped into it. Apart from a new post by my favourite film critic, nothing was outstanding until I reached Lifehacker. The Lifehacker team has just posted a link to a visual media usage rights flowchart created by The Visual Communication Guy. Excellent! Ignorance is no excuse when it comes to image theft and unauthorised use and reproduction of photos. While we're all perfectly aware that when you place something on Facebook, Flickr, or your personal version of Frankie's Funky Photos, there's a real chance that someone will try to use it improperly, the more that we can educate people about the right way to do things, the better. This one, however, was not quite so excellent.

You'll find the original here and the Lifehacker article here.

Apart from the fact that it's far too dense and word-heavy, it contains at least one humongous, glaring, verging on the unforgiveable fault for something that purports to advise on usage rights. Take a look and tell me if you can see it. (And tell me how many others you can see. There are plenty.)

Found it?

If you haven't, because it's a horrid thing to read, here it is:

While the laws about distributing images through social media channels like Facebook, Pinterest, and blogs are still fuzzy, it is generally considered acceptable to redistribute an image that was intended to be viewed publicly by the creator. This is why you will typically find original images re-posted on blogs, news sites, and social media channels even if the person re-distributing the images didn't receive permission to do so.

No, no, no, no, no, no. And for good meaure I'll say it again. No.

Images that are shared on social media aren't free for redistribution unless the creator has expressly said so. I put my images on Flickr and use them here on Photocritic and put them on my personal website to display them, to illustrate concepts, to tell stories. I do not put them on the Intergoogles so that anyone else can make use of them. And you should never assume that anyone else does, either.

The law regarding this is hardly fuzzy about the situation, either. There's been at least one monumental court case that supports this opinion, when photographer Daniel Morel sued AFP and Getty Images after they redistributed his images from the Haitian earthquake, which he'd shared via Twitter, without his permission.

Copyright exists from the moment that someone creates something, whether it's a photograph, a tune, a poem, or a piece of prose. It doesn't matter how a creator wishes to share her or his creation with the world, unless she or he has definitely signed away the rights to it, the rights remain theirs.

To be fair to the Visual Communications Guy, he does state 'My rule above all else? Ask permission to use all images. If in doubt, don’t use the image!' in the post that accompanies the flowchart, but that's not really good enough. It's the flowchart that people are going to share and see, not the article. When incorrect information such as this gains traction, we all suffer. Suddenly what's not right becomes commonly accepted. Or people who were doing their best to not be ignorant are in the wrong when they thought they were doing right.

So I'll say the mantra and everyone can repeat it after me: 'Just because I found it on the Internet, it doesn't mean it's free to use.'

Before entering a competition, read the terms and conditions

This isn't a new drum that we're beating here today, but we think it's a significantly important issue to warrant another parade: competition rights grabs. Or the attempt by competition organisers to inveigle themselves of the right to use any of the images entered into their photographic competitions, for any purposes, with no compensation to the photographer. This reminder comes as I received a call for entries to a competition run in conjunction with an organisation that I respect and trust, and hoped would be above cheap tactics to help magazines or other companies amass a photo library for free. Apparently not. To quote from the terms and conditions:

By entering your photos in the competition you agree to grant REDACTED and REDACTED a non-exclusive licence to reproduce, publish and feature the photos in association with this competition, or for any other purpose, at any time, in any publication, website or other associated media outlets, without compensation. By entering you agree to grant REDACTED and REDACTED an exclusive royalty-free licence to use the full set of images taken on your photography trip [which comprises the prize] for 12 months.

To use images submitted to contests as promotional material for the competition or its future iterations is a reasonable condition of entry; but to demand they be made available for use in any publication associated with the organisers, for any purposes, across all media, and without compensation is, in my opinion, exploitative.

I have written extensively about the damage that these terms and conditions do to both photographers and the photographic industry before now, so I shan't reprise it here. But do bear in mind that if you're seeking your big break from a competition that employs these sorts of terms, you are doing yourself and fellow photographers—amateur and professional—a disservice in the long run. Furthermore, don't assume that just because the competition is being organised by or run in conjunction with a big name that it won't be out to take advantage of you.

The finale to this performance is then: always check the terms and conditions of a competition and if you consider anything to be unsavoury, please don't enter.

Seeing as I've been asked: no, I shan't be naming the competition in question. I'd rather not bring any more publicity to it. Just read the T&Cs!

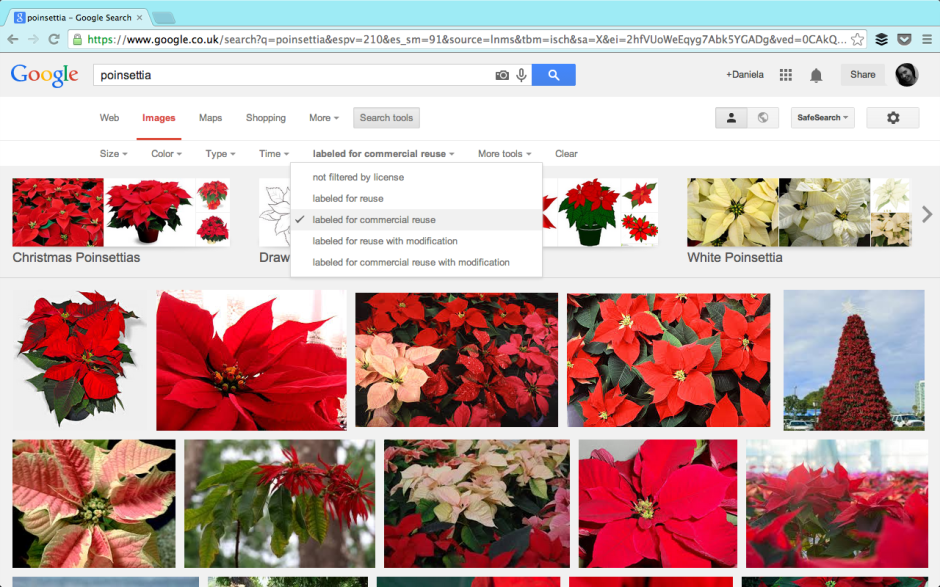

Google's just made it easier to search for images according to licence type

'I found it on Google, so that makes it alright!' No, no, and no. Just because you found an image on the Intergoogles does not make it free to use. How many times have we been through this? I've lost count, I'm sure. It's simple: unless the copyright owner says otherwise, you can't use her or his photos without permission. There are some images that are free to use, but you have to search for them specifically. Thankfully, Google has just made that easier. To be fair, Google Image Search has allowed for refined searches for quite some time, but now they've made it more obvious and easier. Hit the 'Search tools' button and it presents a series of drop-down menus that allow you to select the size, colour, age, file type, and licensing options for your desired image.

Searchers can choose licences covering available for reuse, commerical reuse, reuse with modification, and commercial reuse with modification. So whether you need a poinsettia to illustrate a blog post or a giraffe to add to a surreal composite, the search tools to find them are at your fingertips.

According to the tweet from Googler Matt Cutts, the suggestion for the refinement came from law professor Lawrence Lessig, who's heavily involved in the Creative Commons movement.

Now you can slice/dice Google image searches by usage rights under "Search tools. Thanks to @lessig for the request! pic.twitter.com/8mQxxebTHJ

— Matt Cutts (@mattcutts) January 14, 2014

It will still be incumbent upon anyone wanting to reuse an image to double-check its rights and ensure that they comply with any caveats, for example proper attribution, that might be ascribed to it. However, together with Bing's refined image licence search, there are fewer and fewer excuses of the whine of 'But I found it on the Internet!' when it comes to image theft an misuse.

(Headsup to Dave Stevenson and the Google blog)

Can I use this photo I found on the Internet?

(Or, the non-photographer's guide to image use) It's a truth universally acknowledged that articles, newsletters, blog posts, posters, and basically anything involving blocks of text can be improved upon by the addition of an image. When you're writing about the local cycling club's criterium or producing a short introduction to crochet and macrame, you'll probably want some pictures to illustrate events or to explain techniques alongside your race report or detailed how-to. Can you take a look at the site of a local photographer and use some of his images from the cycle race? Can you conduct a Google Image Search for 'crochet' and download some photos of great examples of people's work?

The short answer is always 'No'. Just because someone has posted an image on the Intergoogles, it doesn't mean that it is free for other people to use. You can't use the china in John Lewis' window display without paying for it first, and a photo on Flickr is just the same. Images belong to the people who create them—or in some circumstances, to their employers—so they get to decide how and when they can be used and what the appropriate fee for using them is. We put them on our websites or on photosharing sites because we're proud of our work and we like to display our capabilities, but it's not an open invitation to filch them.

There are a few exceptions to this rule, but until you know better, work under the assumption that every photographer keeps the tightest control over the use of all of her or his images. Being confronted by an angry photographer wielding an invoice for unauthorised image use is not a pleasant situation, so remember: You can't use other people's photos. Mmm'kay?

For completeness, what are these exceptions you talk of?

Some people are happy to licence their images under Creative Commons terms. Creative Commons licences aren't designed as an alternative to traditional copyright, but a complement. They're easy-to-use copyright licenses that allow you permission to use a photographer's images under terms decided by the photographer. One photographer might let you modify and use his images commercially, but another might say that her images must be attributed, cannot be used commercially, and aren't to be modified. However, not all photographers use Creative Commons terms (you'll see it close to the photo if they do) and if there's no evidence of a Creative Commons licence, assume that you can't use the image.

If you receive an image in a press release or it's made available to you from the press section of a website, this will be free to use in the context of the product or situation. For example, when Olympus releases a new camera, it will make a bundle of images illustrating it available to me. Provided that I'm writing about that camera, I'm free to use them in an article. The National Portrait Gallery will supply a selection of images from each of its exhibitions so that if you're reviewing it or publicising one, you have photos to illustrate the article. But, you can only use those photos in relation to the relevant exhibition and they must be attributed under the terms set out by the NPG.

Some news agencies, for example AFP, are happy for you to use their photographers' images non-commercially and for personal use provided that you credit the photographer and agency and link back to the site. But, some agencies aren't. And you wouldn't want to face the wrath of AP or Reuters. Again, unless you're absolutely certain, assume that an image isn't free to use.

But what if you see an image and want to use it? What should you do?

Get in touch with the photographer! Most of us make it easy to send an email: do just that. We don't bite. Mostly. Tell us who you are, why and how you'd like to use a photograph that we've taken, and ask if you can come to an arrangement. The worst that we can say is 'No'.

That's not so hard, is it?