Whenever I'm asked for quick tips for better smartphone photos, I usually proffer the same advice that I give to any other type of photographer: get closer and tuck your elbows into your body. But with smartphones (or indeed with some point-and-shoots) that first pointer in augmented with an admonishment to avoid digital zoom. So that's do get closer, but don't get closer using the capability that manufacturers have baked into their devices to accomplish it. Get closer, but nix the digi-zoom.

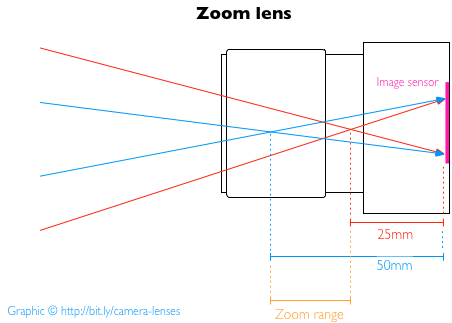

The truth is, digital zoom sucks. One day it might not, but right now it does. It sucks because digital zoom is nothing more than a glorified cropping tool. Whereas optical zoom relies on the physics of lenses to ensure that what you see appears larger or closer, digital zoom simply crops away the extraneous pixels and enlarges those remaining in the picture. While this might get you closer to your subject—and that's rule number one—it has an unfortunate effect on your images.

By enlarging the pixels that are on display, you've degraded your picture quality. You're spreading your information more thinly over the same surface area. It's the technological equivalent of spreading one teaspoon of jam over a slice of toast rather than two. Even if the processor is clever enough to use interpolation to enlarge the image, there's probably still some degradation.

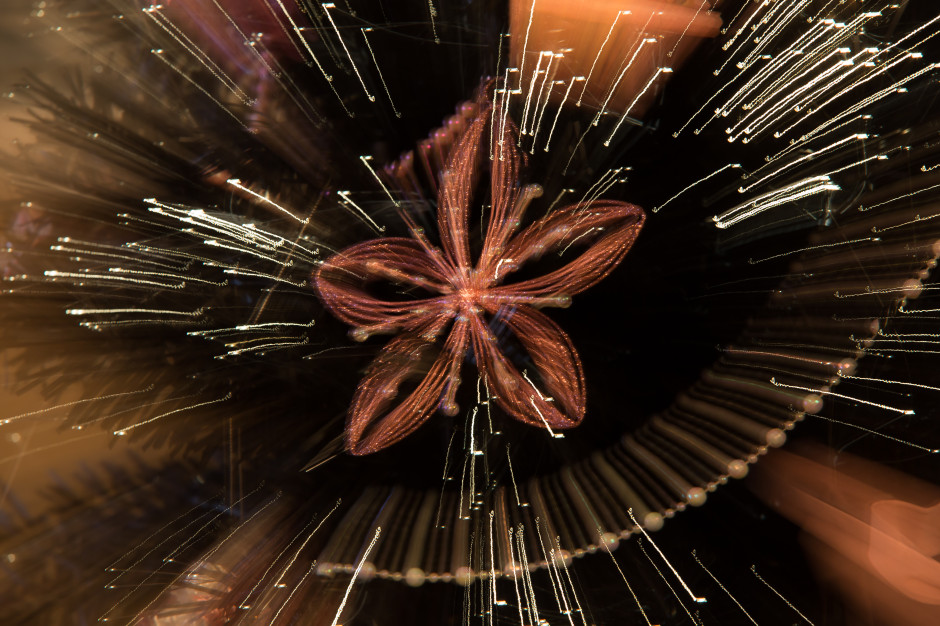

Don't believe me? Have a look at these examples and tell me which is superior. I'll bet you a friendly pound that you prefer the image where I've got closer to my subject using my hands and my feet rather than the slider on my iPhone.

The first step in the art of getting closer is to do so physically: walk in, reach in, lean in. Getting optically closer is your next step. And if you're still not close enough, take the photo with what you've got and crop in after the fact. You'll still be spreading those pixels more thinly, but at least you'll have better control over the final image.

And if you want to get really close, try an Easy-Macro band. It's $15 well spent.