If Jack Frost has been nipping at your fingers, toes, and photos, we have tips to help you get the best pictures you can.

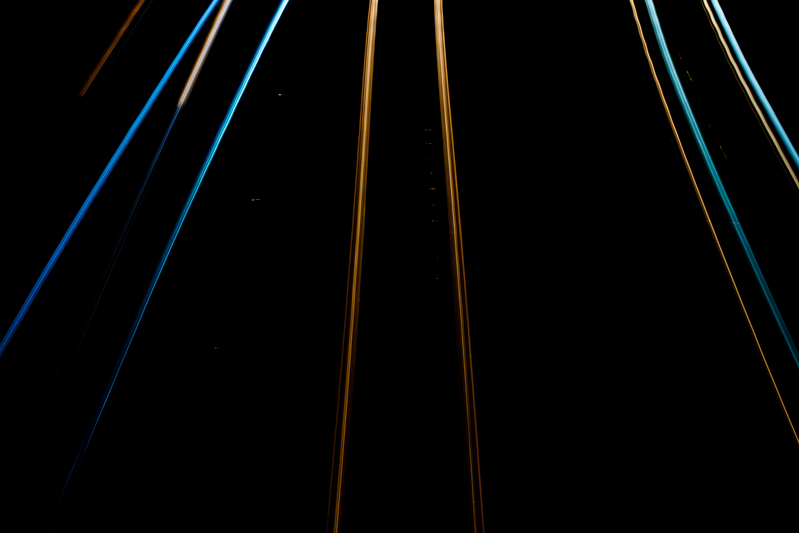

Dare to stray into bulb mode

When setting your shutter speed, have you ever wound the adjustment wheel so far into long exposure that you've gone past seconds and found 'B' or 'Bulb' on your screen? Or maybe you've noticed that you have a 'B' option on your mode wheel, somewhere between Manual and Custom settings? This is bulb mode, and it allows you to control the duration of the exposure for precisely as long as you would like. It's perfect for exposures in excess of the 30 seconds that most cameras have as their longest shutter speed, or for when you need to be in control, for example if you're practising high-speed photography. First, a quick word on why it's known as 'bulb' mode. Haje has a much more thorough explanation here, but it doesn't have anything to do with light bulbs. It's from back in the day when you could control your shutter speed using an air bulb connected to your camera.

When your camera is in bulb mode, you open the shutter by depressing the shutter release button; as soon as you raise your finger off of the button, the shutter will close. Seeing as it isn't terribly convenient to stand with your finger on your shutter release button for minutes or even hours on end—and it's not fabulous for camera-shake, either—most people use bulb mode in conjunction with a remote shutter release. And a tripod, but that's probably quite obvious.

Plenty of remote shutter releases come with a locking mechanism, so that you don't need to hold your finger down there, either. However, if you go for something such as our much-beloved Triggertrap, you can select from a variety of different modes to control your super-long exposure, including a timed release that lets you set the duration of your exposure down to fractions of a second, a star-trails setting, and even a bulb-ramping option to fine-tune exposure during very long time-lapse recordings.

Even if you're shooting at night, your camera's sensor will be able to detect far more light than you think it can, especially with a very long exposure. Consequently, using a small aperture is recommended. If you're photographing during the day, you might benefit from a neutral density filter to prevent unavoidably over-exposing your images, too.

It is worth bearing in mind that using bulb mode can drain your battery enormously. Don't set off to capture star trails with a less-than-fully-charged battery. Take a spare if you have one, too. It's a complete waste to maroon yourself in the middle of nowhere with limited light pollution only for your camera to keel over halfway into the exposure.

Now that you know what bulb is, what can you do with it? Perhaps you'd like to try some long exposures of landscapes? Or maybe capture some smooth, milky-looking water tumbling from a fall. You might want to try your hand at a star trail, or have a go at light painting. You could even grab a flash adapter and have a crack at some high-speed photography and burst some water balloons. So many options presented to you with so much time from bulb mode!

For those days when you need to be in several places at once: multiplicitous images

Multiplicity, or the art of creating images containing several yous, or anyone elses for that matter, isn’t a digital discovery. It’s something that people have been doing for decades: it's remarkably easy to achieve with film. You set up your shot and either you don’t wind on your film before re-exposing the frame with your subject positioned anew in the scene; or you wind on your film and then wind it back again in between shots. The important thing here is to slightly under-expose all of your shots in the sequence to ensure that your final image isn’t an over-exposed white mass.

If you don't happen to have a Holga lying about (they're great for creating multiple exposures), you can do it with a digital camera, too. Depending on the camera you have, you've a few options for creating a multiplicitous image. Quite a few come with a multiple exposure setting now: you determine how many exposures you want to make and the camera will re-expose the same 'frame' in-camera and adjust your expose settings accordingly to ensure that you don't end up with a too-dark or too-light image. Marvellous... if you have a camera that can do that. If not, you'll need to make friends with Photoshop, or a Photoshop-esque editing package.

Before we go any further, it’s important to remind you that achieving a great final image relies on producing a good image in-camera first. It doesn’t matter how ginormous the barrage of editing you’re going to subject your photo to, it’s got to be good from the get-go. This is just the same for a multiplicity image as any other.

When you set out to create a multiplicitous image, your starting point is your concept. Think of the story that you're trying to tell and what you need to tell it. Having a clear plan makes it so much easier when you're shooting the images because—unless it's a distinct element of the story—you need consistency in your images: furniture can't move between shots, the light needs to be coming from the same direction, and you don't want to be flapping around.

When the scene's arranged, set your camera on a tripod, adjust it's exposure settings and focal point, and shoot a 'plate' image. This is a base photo, devoid of the story's characters, onto which you'll build your final creation.

Now you can shoot your series of images containing your subject in as many different positions as your composition merits. I've found it useful to go for more rather than fewer photos; it gives you more flexibility when you compile your final image.

[gallery ids="6703,6704,6705"]

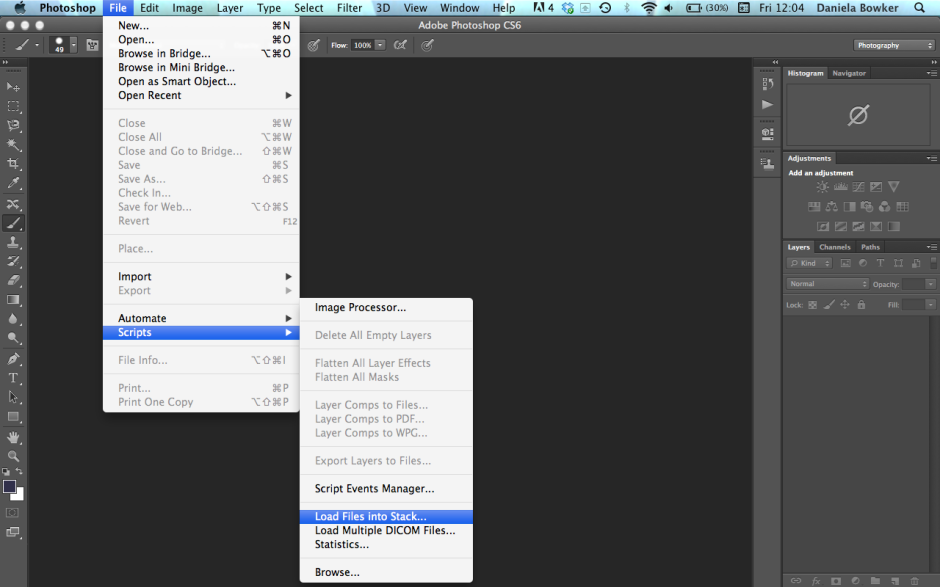

When you've shot your images, import those you think you might want to use into Photoshop using the Load Files in Stacks option (File>Scripts>Load Files in Stack), which should import your images so that they are perfectly layered one on top of the other.

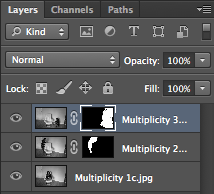

Next apply a layer mask to each of the layers, barring the background image, which should be the ‘empty’ plate.

Using the eye icon on the Layers Palette, toggle off all of the layers from view except Layer 1. Now brush your subject, along with anything like indentations in the chair where she or he is sitting or shadows, out of the image. It's those small details which add credibility to the unbelievable, which is what makes them important to the final composition. And while it might seem counter-intuitive to brush your subject out of the image, it isn't really.

When you’ve disappeared your subject from the scene and you’re happy with the refinement of the edges, invert your selection by pressing Cmd+I on a Mac or Ctrl+I on a Windows machine. The subject will miraculously reappear and the superfluous background will disappear.

Do take care when you're areas where overlapping occurs, because it's here where your image will succeed or fail in its realism.

Repeat this process for each of the layers, toggling them on and off as necessary to decide on which placements you want to keep, and which you wish to discard. I’d recommend saving the image as a PSD file with all the layers intact, which will allow you to revisit it and re-edit as often as your Dr Jeckyll needs to meddle with your Mr Hyde.

When you've settled on a final version, delete the layers that you don't want, save it as a PSD file, and then flatten it and export it as a JPEG image. Ta-dah!