The Unsharp Mask is an old photography trick that has become available to ‘the common man’ through the introduction of digital editing tools such as Adobe Photoshop.

In this article, I will share with you my knowledge and experience of the Unsharp mask tool in the darkroom, and also a thorough introduction to its digital name brother, the Photoshop USM filter.

The name

Traditionally, the sharpening process happened by adding a mask to the original negative. This mask was a blurred (unsharp…) version of the negative, hence the name; Unsharp mask. The final result has nothing to do with unsharp; the whole purpose of this technique is to make an image appear sharper than the negative can convey

Digital USM

So – if you have no idea how to sharpen your photos in a dark-room, why should you care about doing so on a computer? Well, because the computer does the exact same thing, and – despite what you would expect – the computer doesn’t do it better than someone competent in the darkroom. However; The computer offers you the option of a quick undo, which will cut down the learning time a lot.

In this writeup, I’ll be focussing (pun intended) on how things are done in Photoshop – The newest version at the time of writing, to be exact. I am aware that Gimp and Paint Shop Pro can do the same things, and if anyone wants to node the specifics for these packages – feel free.

However; If you are serious about photography, you are not going to get around photoshop – PSP and Gimp are good for a lot, but Photoshop is the industry standard, and it is the package I have been using for years and years (illegaly for ages, legally the past two years or so). If you can get your hands on a copy of PS Elements or PS LE, both of theses should have fully functional USM filters built in, and they are not quite as expensive as the all-singing, all-dancing full version.

(Learning time? But isn’t this a simple tool?)

The USM built into digital image manipulation packages is an extremely powerful tool. If you ask me, it is the reason to own Photoshop (well, that, and levels. And Variations. And CMYK separation tools. And colour proofing tools. Ah, never mind), but like all other powerful tools, it also makes it possible to thoroughly fuck up an image.

On what images to use the USM tool.

Always. Seriously. Even if you only apply it lightly, I have yet to see a picture that didn’t benefit from a run through USM. All digital files need USM applied to them. Even if you have a tack-sharp image on a medium format slide, you will need to apply USM after digitising the image. Why? Because you do; Inherent in the digitalisation tools (digital cameras*, scanners, etc) is a loss of apparent sharpness.

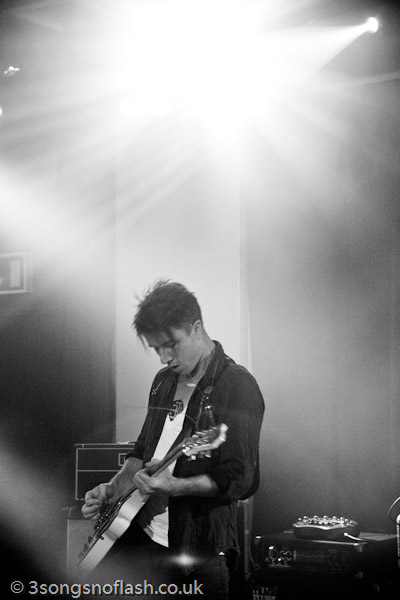

Not convinced how much of a difference USM makes? Check out these before and after images…

Digital cameras and USM

If you feel that you are photo-savvy enough to use the USM tool on a regular basis, you should have a close look at your digital camera. Usually, there will be a setting in a menu somewhere that says “sharpness” or “sharpen”. You’ll want to turn this down as much as it’ll go. Why? All consumer / prosumer digital cameras sharpen the images in-camera. Why? Because the average consumer only sees the pictures that come out of their camera, and if those images are soft, they will run to the manufacturer and complain, out of ignorance. Sad, but true.

Professional cameras (Canon EOS D30, D60, Nikon D100 and the higher-end models) don’t compensate as much, and also offer the option to turn the sharpening off altogether. This is A Good Thing, because it leaves the photographer with full control. And photographers are control freaks (especially anally-retentive perfectionist photographers), so that’s sweet.

When to use USM

When working on an image, you probably have a long series of steps that you go through. Myself, I always do all basic editing (image corrections, manipulation etc) first, then I apply USM, and then I handle the colour corrections. Most design professionals will tell you to do the USM last, while most photographers will make up their own rules (being photographers and all…). The order DOES matter, as the USM filter is destructive (kinda like JPEG compression algorithms), and you will notice a difference in behaviour of the other filters and corrections you do. Give it a try, and see what you prefer yourself.

How to apply the USM filter.

Open a file in photoshop – the larger the file, the better (the more data the USM filter has to work with, the better.) When I am working on seriously high-precision project, I will first take the 6-megapixel image from my camera, interpolate it up to about 18 megapixels, then do the editing and unsharp mask, before scaling it back down. It might be superstition, but the results do seem to look a lot more refined.

Right – after opening the file, crop it. Then, go to Filter -> Sharpen -> Unsharp mask. You should now see a relatively innocent-looking window with three little sliders, marked A, R and T. Amount; Radius, and Threshold.

Let’s start with the last one first. Threshold. I usually leave this on 0, and so can you, most of the time. However, if you have an image with large amounts of noise (esp. if you are working with digital files that have been made a lot brighter, or taken on a high digital ISO value), you might want to set this to somewhere between 1-5. This also prevents small details from being accentuated. On a portrait, for example, using a high threshold might make skin look smoother (than if you didn’t set the threshold), but the hair of the model will not come out as sharp as if you didn’t set a threshold. As I said; I usually leave this on 0, but if you ever need it; Now you know what it does.

The radius is a sneaky thing. In general, the more pixels the picture has, the larger the radius. You’ll want to get sharp images, but not overly so. On a 6 megapixel image, I usually set the radius between 3 and 6 – but it all depends on what you want and need. Experiment. Also, if the image is more blurry than normal, you’ll want a higher radius. If your image is sharper than normal (i.e has already been sharpened in your camera), you might want to use less. To find how to set the radius, set the amount to 100 %, the Threshold to 0, and experiment. Then, set the threshold, and see if you are still happy with the image. Then tweak the amount:

The amount of USM applied is a function of the threshold and the radius (see below). This is usually the last slider you set. In general, the amount should be between 50 – 150 per cent.

When you are happy with the way the image looks, press ‘OK’, and the whole image is processed. Never – EVER – run USM on an image twice. Wanna know why? Try, and you’ll see. It just looks horrible.

For starting values of the USM filter for different uses, try the ones suggested by PhotographyJam:

| Subject |

Amount |

Radius |

Threshold |

| Soft subjects |

150 |

1 |

10 |

| Portraits |

75 |

2 |

3 |

| Moderate sharpening |

225 |

0.5 |

0 |

| Maximum sharpening |

65 |

4 |

3 |

| All-purpose sharpening |

85 |

1 |

4 |

| preparing for Web |

400 |

0.3 |

0 |

Advanced use of USM

Right, now you know how to use the basics of USM, but what else can you do with this tool? Lots. For one thing, you can make a ‘fake’ idea of depth of field: Make a loose selection around the items you want to be in your virtual DOF. Then, ‘feather’ the selection a great deal (selection -> feather). If you are working on full-size files, somewhere between 20 and 60 px feather should do it. Then, apply an USM mask. This sharpens the parts of the image you selected, while leaving the non-selected portions intact. This looks a lot more natural than blurring everything else in the image.

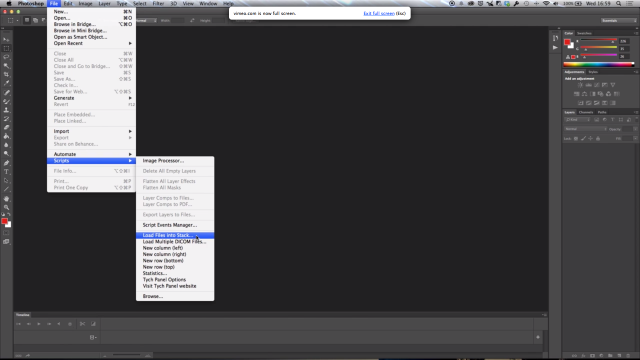

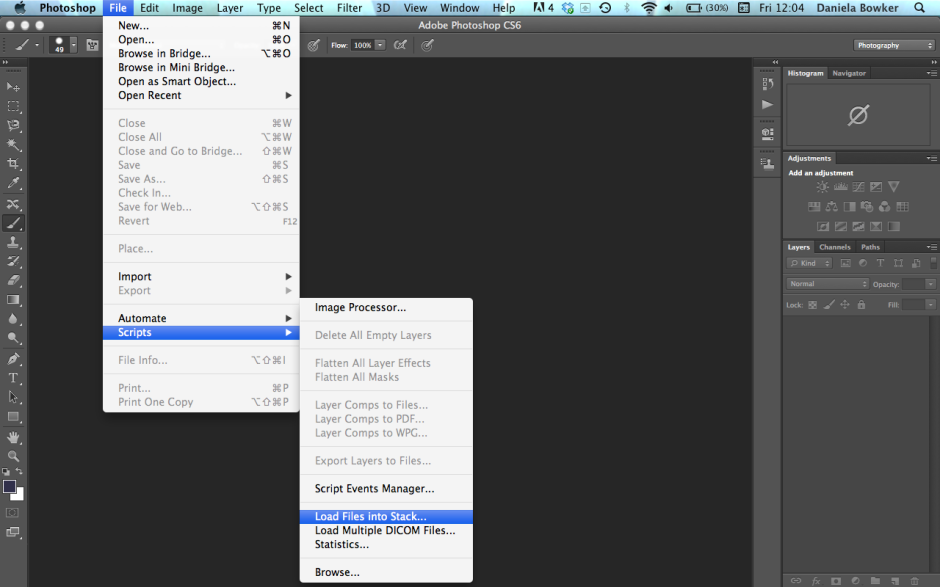

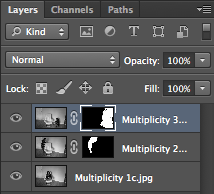

Variable USM: every now and then, you’ll find that an image that has USM applied looks good on one side, but not on another. Hit undo (undo the USM), and duplicate the layer you are trying to USM. Then apply the USM to your new layer. Make a layer mask, and put a gradient fill in this layer mask (or use the same feather technique as above). This way, a portion of your layer will become translucent, but your original layer will still show through. This offers the illusion of a partially implemented USM, which looks pretty damn funky.

Manual USM

Remember what we said about photographers being control freaks? Well, here goes nothing: If you want to manually do an USM filter on your images (either to learn and understand how it works, or for full control), here is a quick and dirty way on how to do it. I am not going into details here – if you are pedantic enough to want to try this, you are probably able to work out how to implement every step, too!

- Make sure your image has a contrast you like. Adjust levels and colours.

- Duplicate your image into a new layer, two times (the ‘background’ layer will be your backup and reference, so you can see the changes by hiding the top layers)

- Blur the top layer a bit (1.5 – 10 px, depending on resolution. 3 is usually a good start)

- Lower the brightness and contrast (approx 25 should do it).

- Subtract this image from your original (Image – Apply image – set source to original, and mode to subtract). This should leave uou with just the unsharp mask.

- Move the unsharp mask layer to the top.

- Invert the unsharp mask layer.

- Set the channel mode of the unsharp mask layer to multiply.

- Merge layers.

- Fix levels / brightness.

- Congratulations.

The strength of the manual mask can be controlled through the amount of blur, the contrast of the layer, and the opacity of the layer. You get an infinite number of toys to play with here – enjoy!

If anything still is unclear (pun intended), feel free to email me!

Do you enjoy a smattering of random photography links? Well, squire, I welcome thee to join me on Twitter -

© Kamps Consulting Ltd. This article is licenced for use on Pixiq only. Please do not reproduce wholly or in part without a license. More info.