Earlier this week an infographic design agency, NeoMam Studios, sent us an infographic about 'smoasting' which they'd produced on behalf of print company Photobox. Once I'd got over the shock of awful elision of 'social media' and 'boast' to form the ghastly portmanteau word 'smoast', there was one particular statistic that caught my eye. Take a look at the infographic and guess which it was.

Despite the prevalence of Instagram, the host of editing features that are built into apps such as EyeEm, Facebook, and Twitter, and the plethora of free-to-download editing programmes, only 28% of photos are cropped or styled in some way? Wow! I am surprised. And it's something I think deserves remedying.

While Team Photocritic advocates getting as much right in-camera as possible—you'll certainly not be able to turn a sow's ear into a silk purse—we're not beyond a little post-processing, either. If it's good enough for Cecil Beaton and Horst, it's good enough for us, too. A snip here and a swipe there can elevate an ordinary image into something a bit more special.

This isn't about air-brushing away half of someone's thigh, but about making minor adjustments to three specific areas: the crop, the colour, and the contrast. Here at Photocritic we call them The Three Cs. They're not complicated and they'll make a world of difference.

Crop

However well composed you think your image is, it will almost certainly benefit from having a few pixels shaved off it. It might be a case of reinforcing the rule of thirds, removing a bit of unwanted background that crept into the frame, or getting a bit closer to your subject.

Being a purist, I tend to stick to traditional 4:3 or 3:2 ratios, but don’t feel limited by my prejudices. Select from any of the standard crops, from square to 16:9, or free-style it to adjust the crop any way you like.

At the same time as cropping, make sure to straighten your image, too. Unless you are deliberately tilting the frame for creative reasons, uprights should be upright and horizons should be level. When lines that are expected to be upright or level are wonky, it has an unpleasant impact on our sense of balance. By correcting wonky lines, you'll produce a stronger image.

Colour

Light has a temperature, and depending on the source of the light, or the time of day if it’s the sun, that temperature will vary. When the temperature varies, so does the colour of the light. As a general rule, we don’t notice the variation because our eyes cleverly adjust to the changes. Our cameras on the other hand aren’t quite so clever.

Have you ever noticed how white objects in your photos can show up with blue or yellow casts? That’s because the white balance in your photo was off.

It's a relatively easy correction to make using the 'Warmth' or 'White Balance' function in an editing programme. If you think the whites are looking a bit too blue (or if an image looks a little 'cold' over all), nudge the slider to the right. If the whites are too reddish in tone, or the photo looks a bit warm, slide it to the right. It's a case of trial and error to make the right adjustment, but the more that you practise it, the better you'll understand the shortcomings of your camera and how it reacts to different types of light.

Now if you want to intensify or tone down your colours, you can do so using the saturation slider. I don't recommend bumping up the saturation too much; it can result in a cartoon effect rather than a photo!

Contrast

Contrast is the difference between the dark and light tones in your photos. Images shot on bright sunny days tend to have a lot of contrast, with dark shadows and bright highlights, but those taken in fog won’t have a great deal of tonal variation and will be low contrast. From time to time, you’ll want a low-contrast image, but, generally speaking, your photos can be improved by increasing the contrast a touch. It brings definition and depth to them.

Don’t go overboard, though, as too much of a good thing can turn bad. You’ll find that if you over-cook the contrast you’ll lose too much detail and end up with an ugly image. Subtlety beats brickbats.

If you use Snapseed to make your edits, it's worth getting to know the ambiance slider, too. I've often found that this is a preferable alternative to the contrast slider.

Anything else?

At this point, any other adjustments are gravy. I'm a fan of Snapseed's 'centre focus' options and often apply one of those. You might want to play with a tilt-shift effect. Or there's the waterfall of filters you can try in any programme, but you might find that you prefer your own edits to prefabricated filters, now.

Oh, and don't forget that it all starts with a decent photo, so check out our eight tips for better smartphone photos, too.

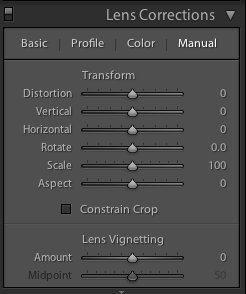

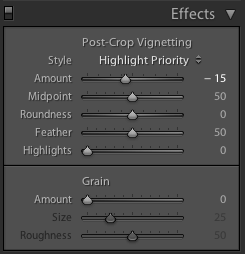

However, there's a lot of fun to be had by simply playing around with other editing packages to produce ethereal-looking images. With something like Lightroom you might want to try:

However, there's a lot of fun to be had by simply playing around with other editing packages to produce ethereal-looking images. With something like Lightroom you might want to try: